Fastnet-79: tragedy and lessons

The crew leaves the yacht «Camargue». The picture was taken by a rescue helicopter pilot. |

In mid-August 1979, huge headlines full of drama appeared in many, even very far from sailing, newspapers and magazines published in different languages of the world: «Racing with death», «There could have been much more dead», «Two days of tragedy on the Toscana», «Is only the elements guilty!» etc. etc.

Sensational reports from the scene, interviews with officials and extensive polemical articles discussed the circumstances and causes of the tragedy that took place during the traditional Fastnet race in the Irish Sea. It was reported about several dozen sunken or missing yachts, about the dead yachtsmen. The press accused the organizer of the competition — the Royal Ocean Racing Yacht Club RORC — of no less than criminal negligence, since yachts of dangerously small dimensions, with poorly trained crews, and without the necessary security were allowed to participate in the race. Even the question of the very right to life of such a dangerous sport as cruising yacht races in the open sea was questioned. Many bitter reproaches were addressed to the rescue service of Great Britain.

What really happened? Why until mid-August 1979, no one opposed yacht competitions in the ocean, although the same Fastnet race, organized every two years, was held for the 28th time! After all, such difficult and risky competitions as a solo race across the Atlantic, the Pacific Ocean, or even around the world, or a round-the-world yacht race, albeit with full crews, are not unusual for modern sailing, but at the most dangerous latitudes for sailing in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans. And then what can we say about the «Mini-Transit» — single races across the Atlantic on mini yachts up to 22 feet long! Is the Irish Sea, protected from the ocean by islands and the European continent itself, more dangerous than, say, the «roaring forties» in the Indian Ocean!

It became possible to answer these questions only after some time after the events of the tragic night from 13 to 14 August. It was possible to clarify a number of details, to establish the actual size of the disaster. In a calm atmosphere, without the pressure of the public and the noise of the press, the persons involved in sailing were able to analyze what happened.

Storm in the «Cornwall Triangle»

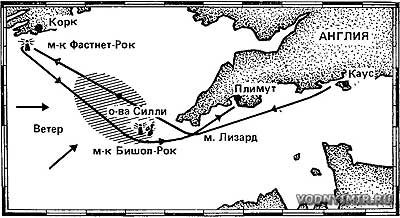

On Saturday, August 11, with a 3-4-point westerly wind, a fleet of 306 yachts started in Cowes in order to follow the race route familiar to many yachtsmen to reach the lonely Fastnet Rock rock off the southern coast of Ireland, turn back and finish in Plymouth. At intervals of 10 minutes, yachts of seven different classes went to the track, starting with IOR class V (racing score 6.4-6.98 m; length — about 10 m) and ending with zero — ocean yachts of the maximum sizes allowed under IOR rules (racing score — up to 22 m; length — up to 24 m). On Saturday and Sunday, the entire fleet slowly moved along the southern coast of Great Britain with weak winds from the west and somewhat reduced visibility. Nothing, however, foreshadowed the deterioration of the weather. When on Monday night the weather stations broadcast a forecast on the radio that promised wind strength up to 5-6 points, most of the yachtsmen were even happy about it. After all, yacht crews had to deal not only with a weak wind, but also with a strong headwind; in order not to drift back, some ships even had to anchor in anticipation of a stronger wind.

The scheme of the Fastnet race distance. The place of the greatest number of yacht accidents is highlighted. |

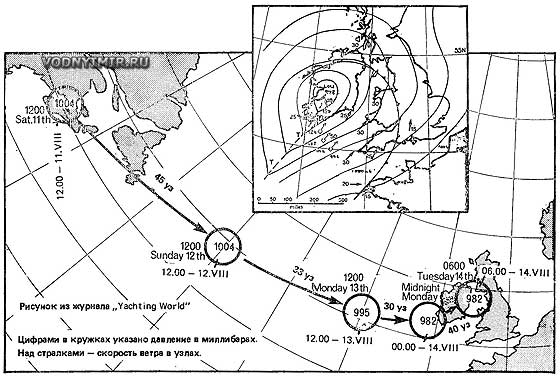

Almost simultaneously with the start of the Fastnet race, a cyclone was born far away from Cowes — over the shores of Canada — which began its movement across the North Atlantic at a speed of about 1,000 miles per day. The pressure in the center of the cyclone dropped to 1006 mb (about 755 mmHg); as it moved towards the shores of Europe, it gradually decreased. Thanks to the information transmitted from artificial Earth satellites and processed on electronic computers, forecasters of both continents had the opportunity to monitor Cyclone Y (prosaic names like this are usually given to irregular disturbances of the atmosphere, unlike hurricanes operating on relatively constant routes).

This information included photos of clouds over any part of the earth's surface and the location of isobars. With such data, the «weather gods» calculated and plotted on the synoptic maps the expected trajectory of the cyclone over Europe. Cyclone Y, according to their calculations, was supposed to sweep over the Bay of Biscay and Spain and only partially touch the western part of the Irish Sea with its wing. Pressure was expected to drop to 998 mb (750 mmHg) over the Bay of Biscay in the center of the cyclone, which did not inspire much concern.

However, neither satellites nor the latest computers this time did not help forecasters to unravel the insidious nature of Cyclone Y. Approaching the shores of Ireland, warm air masses coming from the western coast of the Atlantic Ocean collided with a cold front coming from Iceland. In a short period of time, the pressure in the center of the cyclone dropped to 993 mb, the trajectory of Y deviated sharply from the route drawn by forecasters to the north, and the cyclone passed just over the very center of the Irish Sea — between the Scilly Archipelago and the Fastnet Rock.

A diagram of the movement of cyclone Y across the Atlantic Ocean. A fragment of the synoptic map for the area of southern Great Britain and Ireland at the time of the apogee of the storm 04.00 on August 14, 1979 is shown separately. |

Here, by the beginning of the storm, the bulk of the racing yachts turned out to be. A 45-60-knot wind (25-32 m/s) struck them with terrible force, gradually changing the south-westerly direction to the pure west. Accordingly, the yachts sailing under spinnakers and bloopers replaced them first with Genoese, and then with storm staysails, reefing the grottos. And by the middle of the night from Monday to Tuesday, this became too much for the vast majority of relatively small and medium-sized vessels; their crews preferred to completely remove the sails and drift on floating anchors or to escape from the storm to the nearest ports of refuge.

To the credit of meteorologists, it must be said that already at 14.00 on Monday, when Fastnet had just rounded the first two yachts — these were the Maxi yachts Kialoa (USA) and Condor (Bermuda), they gave a storm warning through the BBC broadcast radio stations: «Salti, Fastnet, Shannon. A storm of 8 points is expected from the south-west».

Yachts «Villivav» and «Win-na-Mara IV» in a fresh breeze. Photo by Patrick Roach. |

At that time, the Fastnet Rock lighthouse had excellent clear weather with a westerly wind not exceeding 4 points and a long wave coming from the ocean. And a few hours later, the sea around the rock turned into a hellish cauldron, in which 10-meter waves raged, covered with a continuous veil of white foam...

At 16 o'clock, the lighthouse keepers reported that a 7-point wind was blowing in their area and a wave was rising, which was superimposed on an established wave. It was in the excitement that the main danger lurked for light sports boats caught in the «Cornwall Triangle», as the fatal area of intensive rescue operations was later called. A gentle ocean wave falling into the relatively shallow Irish Sea (its maximum depth does not exceed 180 m, and on banks near Scilly and Fastnet Rock it is measured in several fathoms) becomes very steep here. With the remaining height of 9-11 m, the wavelength is greatly reduced, its crest hangs over the sole and collapses from this height in a multi-ton bulk. A yacht that has climbed such a ridge can simply fall off it, flying through the air a few meters.

Judging by the measurements of the period of excitement that played out that night near the Fastnet, the wave length was no more than 75 m, i.e. it turned out to be 2-2.5 times shorter than in the open ocean. The situation was further complicated by the fact that the storm had gained its full force in the dead of night, when it was very difficult for the helmsmen to follow the oncoming ridges and maneuver between them.

It's not for nothing that Robert James, the skipper of the «Great Britain II», who participated in the round-the-world marathon, said after the finish of the memorable Fastnet race: «The storm on August 14 was the worst I've ever seen, and I've twice circumnavigated the globe on a yacht!»

At 22.30, the new forecast promised further strengthening of the wind near Fastnet Rock to 10 points. This storm came shortly after midnight, when the «Golden Apple», the first of the yachts participating in the Admiral's Cup races, rounded the rock. By 2 a.m., when Eclipse was making a turn around the lighthouse, the storm had already reached its maximum strength; only the smallest storm staysail could be carried on the yacht.

The south-west allowed us to go to the lighthouse in Gulfwind, and return to Cape Lizard on the same course. And yet, the share of the yacht crews, who are just getting out to the lighthouse, has been much more severe than those who have already returned.Duel with the sea

The duty officer of the Royal Navy rescue station in Caldrose — on the Cornwall Peninsula — was whiling away the usual «dog» watch when at 1.40 an anxious voice weakened by distance and interference sounded in the speaker: «Mayday!». The crew of the yacht, on which the rudder was broken by the storm, asked for urgent help: the waves brought down all their strength on the helpless vessel, tore off the hatch cover, threatened to flood...

Then distress signals began to arrive one after another, calls for help literally filled the air! They were mainly served from small yachts that had not yet reached Fastnet Rock and were located to the northwest of Scilly at a distance of 15 to 100 miles from Cape Lizard.

Yachts at the exit of the Strait of the Solent. Photo by Patrick Roach. |

The rescue station was unable to provide effective and quick assistance to everyone in need at once, especially since most of its personnel were on vacation. At first, only two helicopters on duty were used to rescue the yachtsmen. It took some time to transfer five more helicopters, six ships of the British Navy, a Danish destroyer, an Irish ferry and several fishing trawlers to the area of the «Cornwall Triangle», as well as to attract all-weather bots of coastal rescue stations in southern England and Ireland to rescue operations. Many of these small boats, whose dimensions were no larger than those of the yachts they rescued, had to work in stormy seas for 36 hours, removing people and towing damaged vessels to ports of refuge. With the onset of dawn, four jet planes were constantly barraging between Scilly and Fastnet Rock, which guided helicopters to ships in distress and life rafts.

And yet we can say that the yacht crews had to face off against the raging sea in a brutal duel. And people did not always come out of this fight victorious.

Shortly after midnight, a huge wave overturned the yacht «Trophy» (III class IOR; length — 11.3 m). With yachts equipped with a heavy false keel, even in the open ocean, this happens extremely rarely. However, during this one terrible night, a total of 17 keel yachts were capsized in the stormy Irish Sea (although only one of them belonged to the three senior classes according to IOR, all the other cases fall to the share of yachts of three junior classes — III, IV and V).

«Trophy» (like all the rest of the capsized yachts) immediately got into a normal position, but through the opened flap of a similar hatch, water managed to fill the interior; there were damages in the mast and rigging. Eight crew members hurried to switch to an inflatable life raft, but as soon as they moved away from the side of the yacht, it was covered by the crest of a wave and four yachtsmen were torn off at once. Then the waves turned the raft over four more times, playing with it like a ball, and all this time people were holding on to it with great difficulty. However, after the fifth coup, two of those on the raft were thrown so far away that there was no way to help them. The impact of the next wave tore the raft in half. Five people grabbed one part of the raft, the other supported the sixth.

It was only at dawn that the helicopter managed to find what was left of the raft among the huge waves and pick up — it was far from easy — five of the «Trophy» crew members who were still alive: the sixth died of hypothermia.

The wave also overturned the yacht «Camargue» (III class IOR; length — 10.2 m). Three watchmen were overboard. Thanks to the fastened carabiners of the safety belts, they were quickly lifted onto the deck. But the ordeal did not end there. About an hour later, the yacht was again tipped up by the keel. Exhausted yachtsmen barely lifted on board their comrade, washed away by the wave. It was decided to call a helicopter by radio. The pilots were able to find the emergency yacht, but they could not hover exactly over the deck dancing on the waves: the yacht's mast described arcs of 45° from side to side. I had to give the rescued the command to jump into the water with signs. This was the only way out — the yachtsmen understood this perfectly well, but none of them could decide to leave the «Camargue», and the captain had to push them into the sea one by one.

The half-ton «Gringo» tipped over not even twice, like the «Camargue», but three times! The last time the mast was broken and the deck was damaged. The crew left the yacht on a life raft and spent six hours waiting for help...

On the half-ton «Magic» wave tore off the steering wheel. For 10 hours, the sea tossed the helpless yacht, which neither the floating anchor nor the smallest staysail in area could help (they tried to carry it in order to reduce the pitching of the vessel to some extent).

Several times the captain gave a distress signal, but the rescuers were only able to convey a few encouraging words: they did not have time to catch people who had already fallen into the sea and remove crews from ships already flooded with waves... Rudders were broken on a total of 11 yachts! The largest of them was the «Golden Apple» with a length of 14.3 m. Driven by Olympic champion Rodney Pattison, this yacht, according to the calculations of the skipper, was supposed to finish first among the «admiral» yachts. The «Golden Apple» was speeding at a speed of 14.5 knots and was 40 miles from the Isles of Scilly — in the heat when the «heavy-duty» carbon fiber rudder baller broke. The crew gave the sail from the stern as a floating anchor, having made a hole in its bottom, tried to somehow control the yacht with the help of long ends etched aft, but in spite of everything the ship began to drift to underwater reefs. On the evening of August 14, a helicopter hovered near the «Golden Apple» and the yacht's crew, who had moved to their life raft, was lifted onto a rotorcraft.

Late at night — in the midst of a storm — red rockets were spotted from the French yacht Lorelei, which took off away from her course. The yacht was sailing under a muffled reefed mainsail and could hardly cope with the wave itself, but the captain, without hesitation, turned to help those in distress. They turned out to be seven Englishmen from the yacht «Griffin» (class III, length — 10.2 m), which, after a full 360° rotation, quickly filled with water and went to the bottom. The yachtsmen managed to get on the raft, but it was soon crushed and overturned. People could barely hold on to its bottom; from time to time, another wave threw someone away, but thanks to the safety ends, everyone somehow managed to stay near the raft.

Yacht «Ariadne» with a broken mast, abandoned by the crew. The picture was taken from a helicopter. |

For about an hour, the «Lorelei» maneuvered under the engine, trying to approach the raft, until finally it was possible to stop two or three meters away and with the help of abandoned lines with rings to lift everyone on board. The Englishmen who spent 2.5 hours in the water were dressed in dry clothes and sat on the pier (to lower the center of gravity of the yacht); later the rescued were transferred to one of the trawlers.

In the afternoon, the rescue operations management center began receiving messages from fishing vessels and Navy ships picking up yachtsmen from inflatable rafts, removing from yachts that had lost masts (there were a total of eight) and rudders. A French trawler rescued seven people from the drowned «Carioti». Five people were removed from the «Tarantula» that had lost its mast. Only four people were rescued from the capsized «Ariadne» — three were missing, one died of hypothermia. The entire crew of seven people was removed from the Bonaventure, which was badly damaged after the capsizing, etc., etc.

In total, 136 people were rescued in this way — removed from rafts and yachts, 75 of them with the help of helicopters. The sea took the lives of 15 yachtsmen who were washed off the decks of yachts during a storm or died when rafts were damaged.

The race continues

Meanwhile, the race continued.

Already on the way back to Plymouth, a sharp duel took place between the American «Kialoa» and the «Condor», on which the crew from Bermuda was traveling. As soon as the yacht passed the traverse of Cape Lizard, a spinnaker was installed on the «Condor», despite an 8-point wind. The speed immediately increased dramatically, the yacht went into surfing mode. Several times the lag arrow stopped against the number 27 uz, and once the speed reached a truly incredible value — 29 uz! The helmsman could hardly manage to control the yacht. Once, with a strong roll, the rudder feather was bared and the «Condor» rushed so sharply to the wind that the spinnaker «stuck» to the mast and shrouds, and the yacht took the reverse gear. Putting the ship back on course and filling the spinnaker with wind, the crew took the yacht further.

«Condor» finished first on August 14, setting a new time record for the 605-mile Fastnet race distance: 71 hours 25 minutes 23 seconds. «Kialoa» also exceeded the old record.

Crossing the «Cornwall Triangle», the crew of the «Condor» could not participate in rescue operations, but through its powerful radio station duplicated distress signals from small yachts, maintaining constant communication with the rescue service of the Navy.

«Morning Cloud», which took 43rd place taking into account the handicap, is coming to the finish line. Photo by Patrick Roach. |

By noon on August 15, six yachts of the I class finished in Plymouth, then the participating yachts of the Admiral's Cup began mooring in the harbor. By the way, Class 0 and Class I yachts suffered the least from the storm: out of 14 maxi yachts, only one came off the course, and out of 56 Class I yachts, 36 successfully finished. Not a single person was lost from these vessels. In total, only 85 yachts returned to Plymouth: 5 yachts sank, 19 were abandoned by their crews in damaged condition, the remaining 197 left the race and took refuge in safe harbors.

Only one yacht out of 58 declared finished in the V class. «Essence» (type «Contess-32») came to Plymouth on the night of Friday to Saturday, August 18. On Monday evening, the crew of this yacht met a 9-point storm under the reefed mainsail and storm staysail. Having a pennant wind at a heading angle of 40°, the «Essence» made 5 knots, despite the rapidly growing waves. At 2 a.m., the yacht capsized; when she got up, the crew had to clean up the staysail that had been blown to shreds. For a day the yacht went under one reefed mainsail until the wind began to subside. The fastnet Rock «Essence» passed at 10.05 on Thursday on a beautiful sunny day under full sails and with a 2-point wind: only a multi-meter ocean swell reminded of the storm experienced ...

Fastnet lessons

The storm race has long been an object for study by all organizers of such cruising yacht competitions, yacht designers, as well as bodies overseeing the safety of navigation and the construction of new ships at shipyards.

The most complete information about all the circumstances of the tragedy is contained in the materials of the survey of 3,000 participants of the Fastnet race. The RORC secretary handed each of them a detailed questionnaire — three pages of typewritten text.

In addition, all yachtsmen were asked to make suggestions on improving the design and equipment of yachts, organizing races, and ensuring their safety.

The processed data has not yet been received by the editors of the collection, but, nevertheless, a number of obvious conclusions can already be drawn.

First of all, it is impossible not to note the exceptional meteorological conditions that arose in the Irish Sea on the night of August 14, when so many yachts turned out to be in it at the same time. And yet — 28% of the total number of participating yachts (almost a third) were still able to successfully complete the distance and finish in Plymouth! Only 8% of ships were abandoned by their crews or drowned. The rest, as we already know, have dropped out of the race for one reason or another. The main reasons for the gatherings were insufficient psychophysical training and sea experience of the participating athletes (on many yachts, for example, there were family crews), breakage of the mast and rudders.

Often, yachtsmen, when a yacht received certain damages, were in a hurry to entrust their lives to life rafts, instead of fighting for the survivability of the yacht, which is an immeasurably more reliable floating means. It is noteworthy that the yachts «Trophy», «Camargue», «Magic» and «Golden Apple», hastily abandoned by the crews, after the end of the storm were found floating in the sea with an almost normal draft — according to their KVL — and were quietly towed to ports.

An instructive case occurred with the English yacht «Ganslinger». After capsizing, the yacht stood on the keel with a broken rudder and a fair amount of water in the hold. The crew decided that it was urgent to leave the yacht, and launched an inflatable raft. One of the yachtsmen moved onto it to receive a radio, a supply of missiles and other supplies, but suddenly the line connecting the raft to the yacht broke. Seeing that the raft was quickly drifting away, the yachtsman jumped into the water, but it was too late: he could neither swim to the yacht nor use the help of his comrades...

The people who remained on the yacht without a raft realized that now their only salvation is to fight for their vessel to the end. Armed with buckets and pans, they quickly pumped out the water. Then the yachtsmen built an emergency rudder and eventually brought the yacht to the port on their own. The only help they accepted from the outside was to call a helicopter to transfer to it a sailor who had received serious injuries during a yacht flip.

We emphasize once again: it is noteworthy that the smallest number of incidents occurred with the yachts participating in the Admiral's Cup races. The most qualified crews gathered here, having previously passed the qualifying races at home. And it is not surprising that of the 54 «admiral» yachts that started in the Fastnet race, only 13 left the race and only one («Golden Apple») was abandoned by the crew.

There were some shortcomings common to most courts. Thus, the reliability of a number of yacht equipment units turned out to be insufficient, in particular, the reliability of similar hatch closures. When turning yachts upside down with the keel, sliding flaps (this is still the most commonly used type of closure!) they simply jumped out of the grooves, opening access to the water inside the vessel; when the yacht stood on an even keel, it turned out that the flaps were carried away by a wave, and the water rolling onto the deck freely flooded the interior. Heavy batteries and counterweights of galley plates, fire extinguishers and other heavy objects that destroyed cabin equipment and posed a danger to the crew were torn from their mounts.

In some cases, the strength of the hulls of modern lightweight yachts turned out to be critical, in the design of which the designers pursued the main goal — to achieve maximum efficiency in racing. As a rule, these buildings were made using the latest high-strength materials and without taking into account the time-tested Rules of classification and construction.

Insufficient supply of yachts with storm sails, the absence of floating anchors on many of them, the absence of emergency closures for all openings in the deck and deckhouse were revealed.

The exceptional importance of two-way radio communication was once again confirmed. It was the presence of transmitters on yachts that made it possible to distribute most effectively over a relatively large area of the «Cornwall Triangle» those modest funds that the rescue service center had at a critical moment.

The Fastnet epic became the largest operation for the British Coastal Rescue Service since the end of World War II. It is impossible not to agree with the general opinion of experts that, in general, the actions of the rescuers were quite effective (primarily due to the wide interaction of helicopters, ships and vessels involved in rescue operations).

The deaths of people were almost exclusively associated with the abandonment of yachts by them and occurred most often when yachtsmen found themselves on inflatable rafts. In extreme conditions, inflatable rafts proved to be an insufficiently reliable lifesaving means. They were turned over by the wave, they were torn apart, their awnings could not stand. The supply of rafts in some cases turned out to be incomplete (and our yachtsmen often dismantle the raft to reduce its weight and dimensions when folded). For example, the crew of the «Griffin», once on the raft, did not find on it either the required supply of drinking water and food, or a floating anchor, etc. When capsizing yachts, there were cases of spontaneous opening of rafts.

In their speeches to the press, the leaders of sailing in a number of countries and the captains of yachts noted the particular importance of timely notification of ships participating in sea races about the upcoming weather changes. In the case of Cyclone Y, the gap between receiving the forecast from the meteorological center and transmitting it to the BBC was from 1 to 3 hours — the time during which the situation in the water area of the races changed significantly.

The article is based on reports by Jonathan Estland (Ajax News) and publications in magazines: «Yachting World», «Yachts & Yachting» (England), «Modern Boating» (Australia), «Vela e Motors» (Italy).

In the section «Motorboats, boats, yachts — miscellaneous, reviews, tips»

Share this page in the social. networks or bookmark: